HN: There are different approaches to the elevating of animal rights in human society. Appealing to health, to compassion for suffering, to the impact of animal agriculture on the climate emergency – and, in your article, to the wellbeing of humans themselves? Which could prove the game-changer?

Dr Wills: I have already highlighted the climate emergency hook, but I think the public health and animal suffering dimensions, as well as the connection between them, are also important. Two cases from 2020 highlight the potential of making these links. The first was the Pakistani case of Islamabad Wildlife Management Board v. Metropolitan Corporation Islamabad, which was formally about the appalling conditions of captivity for the nonhuman inmates of Islamabad zoo, but in an extraordinary judgement, Justice Minallah explored broader themes of human hubris and arrogance, COVID-19 and the interconnections between human rights, animal rights and environmental protection. It’s a beautiful and powerful judgement even non-lawyers will appreciate.

The second case of note is Mckiver v Murphy Brown. This was a successful nuisance lawsuit brought predominantly by poor people and people of colour against an industrial pig ‘farm’ in North Carolina. What was particularly striking in the ruling is the separate, concurring opinion of Judge Wilkinson who excoriated not just the farm’s trampling over the rights of its poor neighbours but also the ‘deplorable conditions of confinement’ for the pigs, noting that the model of industrial exploitation exemplified by the faculty ‘created serious ecological risks that, when imprudently managed, bred horrible outcomes for pigs and humans alike.’ These two cases are model examples of how courts can deliver rulings that span environmental, social justice and animal rights issues. They show what I attempted to highlight in my original article: animal rights and human rights are not zero sum, they are intertwined.

HN: What are the external conditions that could accelerate change? You mentioned Covid. How has that influenced arguments? What are the other external conditions that we should be considering?

Dr Wills: Yes, COVID and the risk of future zoonotic diseases has the potential to be a game changer. After all, it’s not just wet markets in China that pose threats for future pandemics; Western torture farms in which animals are reared in cramped conditions, living in their own excrement and urine in windowless, unventilated warehouses are breeding grounds for disease. And zoonotic disease is a walk in the park compared to the potential consequences of antibiotic resistance in humans arising from their routine use for ‘livestock’.

Even setting aside the animal rights and environmental arguments, the public health case for wiping out torture farms is obvious. Yet, left to their own devices, governments have shown that they will continue to support Big Ag. We need a social movement to fight to get rid of them. We need vegan, environmentalist, animal welfare, animal rights and public health activists to work together to bring about this change.

Another important external condition is the availability of alternative protein sources palatable to individuals raised on animal flesh and secretion-heavy diets. Once people stop eating animals, the material conditions for the abolition of animal exploitation will be in place. The range of plant-based alternatives to flesh and secretion products is now unbelievable. This year, a record half a million people signed up for Veganuary and the shelves of supermarkets and menus of restaurant chains are awash with vegan convenience foods. Last year also saw the first commercial availability of cellular meat in Singapore and Israel. Though not entirely unproblematic from an animal rights perspective, cellular meat has the potential to spell an end to animal farming as we know it, which can only be a good thing.

HN: Animal suffering is deliberately hidden from the vast majority of people. If they could see it, would they act?

Dr Wills: I certainly think that many would at least not consume the products of the industries responsible, although exposés alone are not a panacea. People have a variety of psychological defence mechanisms to manage or ignore inconvenient truths. But while giving slaughterhouses glass walls probably wouldn’t, as Paul McCartney claimed, make everyone vegetarian, raising awareness of the plight of nonhuman animals trapped in systems of exploitation is likely to help contribute to a moral awakening for many.

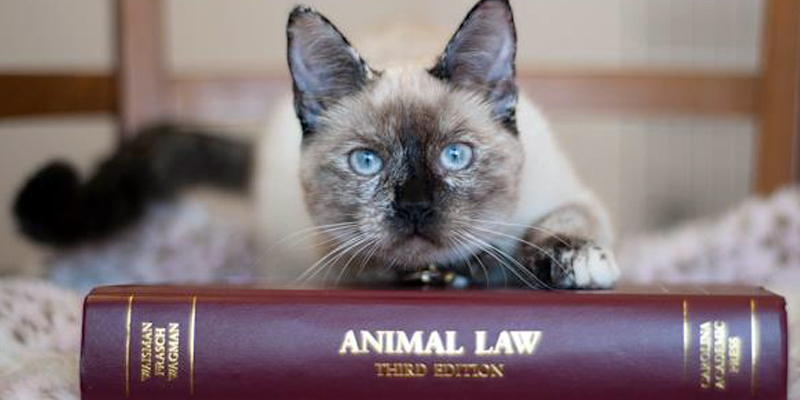

The animal exploitation industries are aware of all this, which is why they are doing everything in their power to keep animal abuse hidden from the public. A particularly pernicious legal means they’re deploying to this end is so-called ‘ag gag’ legislation which imposes legal sanctions of varying degrees of severity on undercover investigators who expose the routine atrocities in torture farms and killing factories. Animal lawyers in the US have won a series of legal victories against these anti-whistle blower laws on First Amendment grounds, but in recent years these laws have spread to Canada and Australia too. They will be a key legal battleground for the animal advocacy movement in the coming years.

HN: On one hand is anthropomorphism; on the other, objectification. Both have issues – but does anthropomorphism at least hold within it the possibility of empathy?

Dr Wills: The biggest problem currently is ‘anthropo-denialism’, the human tendency to ignore that we are animals and the other species are our evolutionary, biological and psychological kin. We share many capacities with the animals we exploit – our emotions, our vulnerability, our desires, our preferences, our relations of care – yet people chose to live in denial about these connections because they impugn present practices. Psychological research by Brock Bastian and his colleagues has demonstrated a link between seeing animals as food and viewing them as having diminished mental lives. It’s much easier to think of the slab of flesh on the plate as coming from a simple life form rather than an emotionally complex individual with relationships and a capacity for pleasure and suffering.

Fostering an empathetic connection to the other species is crucial for the animal rights movement and this is often a challenging thing to do in the legal sphere whose official discourses tend to emphasise rationality, detachment, abstraction and universalism over emotions, relationality, situatedness and particularity. An interesting trend in animal legal advocacy in the US, Canada, Colombia, Argentina, India and Pakistan that potentially could redress the law’s tendency to abstraction is efforts to enforce the rights of particular animals in the courts – animals with names and biographies. Telling stories about animals as individuals rather than as tokens of abstract categories may go some way to promoting empathy through the legal domain.

HN: We sense a coming-together of the animal rights and human rights. Is this the case?

Dr Wills: Yes, I think so. Back in 2018, animal advocacy lawyer Jay Shooster wrote an article about how human rights groups are beginning to support animal rights. Similarly, in the animal rights movement, there have been efforts to make the movement more inclusive, more diverse and to avoid campaigning in ways that reinforce oppressive attitudes or practices against humans. There is still much to be done in both directions but at essence, the human rights and animal rights movements should be natural bedfellows. As Martin Luther King said, injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.